Camila GutierrezPh.D. student in Comparative Literature and Visual Studies at Penn State

This paper was meant to be a longer study regarding moments of rupture in graphic narrative, and how those moments open a space for intersectional aspects of the narrative to surface. By rupture, I mean moments in which the conventional linearity and sequentiality of comics is momentarily abandoned, or moments in which seemingly decorative but actually meaningful elements disrupt the page. If conventional comics are a woven pattern of panels and gutters, these moments are ruptures through which the spun fibers are visible for a moment. The knit fabric of the page reveals the twists of a gendered life, of an ethnic lineage, or a distant culture. By reading the graphic novel Skim by Canadian Japanese authors Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki, and the comic “Flies on the Ceiling,” by Chicano author Jaime Hernández this paper discusses how the language of comics may illustrate alternative epistemologies or women’s epistemologies as coded in non-linear languages. Scott McCloud has named some of the techniques featured in these comics as “aspect to aspect” transitions, or “non sequitur.” Thierry Groensteen in turn has referred to how arthrosis may replace sequentiality in narrative moments of this kind. In line with McCloud’s and Groensteen’s formal language, I start from the premise that these works are conveying alternative ways of knowing that may seem unstructured from the point of view of logic and sequentiality. The comics illustrate a kind of alterity that concentrates on moments of intersectional tension in the lives of their women protagonists. In these moments, the artists introduce iconographic references that stress the close connection between these women’s gender/sexuality and their ethnic backgrounds.

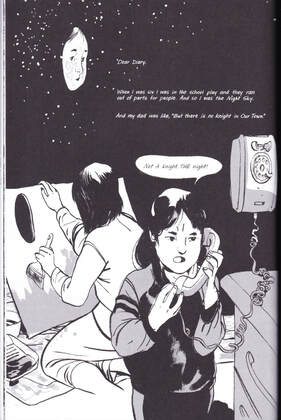

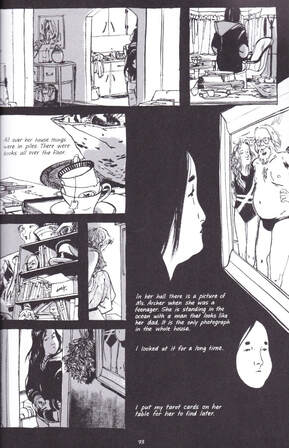

Skim, by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, has several references that intermittently focalize the story through premodern and modern Japanese culture and literature. Contextualizing these tropes in Japanese women’s culture, one may read Skim as a story about complex forms of female homosociality rather than lesbianism as understood in the West. There is, for example, the drawing of Kim, the protagonist, as a premodern Japanese beauty –her face framed by straight black hair, her eyebrows small, her cheeks full and her mouth tiny and delicate. At multiple times, her face evokes an otafuku mask (a theatre prop that in turn relates to an 8th-century female deity who lures goddess Amaterasu to come out of a cave –as per Nara period mythology). Pages 48 and 73 show Kim as a floating otafuku against a black background. Her location obeys no paneling and no divisions. Her face floats like a Japanese mask through the page as she works through unpleasant emotions. The sequence is ruptured, the page becomes fluid, and so readers access the protagonist’s inner realm. In these and other floaty moments where sequentiality seems suspended, Kim is shown struggling to find comfort or happiness in her relationships; her social world affected by a pained interiority. Kim may not be the charming dancer capable of captivating a goddess. But she is empathetic to other women’s complex emotions –to their grief, their disappointment, their growth. The melodramatic tone of Skim’s girl-girl connections resonates with S-kankei literature from the early twentieth century, which thematizes intense relationships between—rarely sexual, albeit zealous and passionate. Understanding this and other examples of rupture and culturally specific nuances of Skim’s imagery may interiorize readers into the realm of Japanese girls’ love and intimacy beyond the limited scope of Western homosexuality.

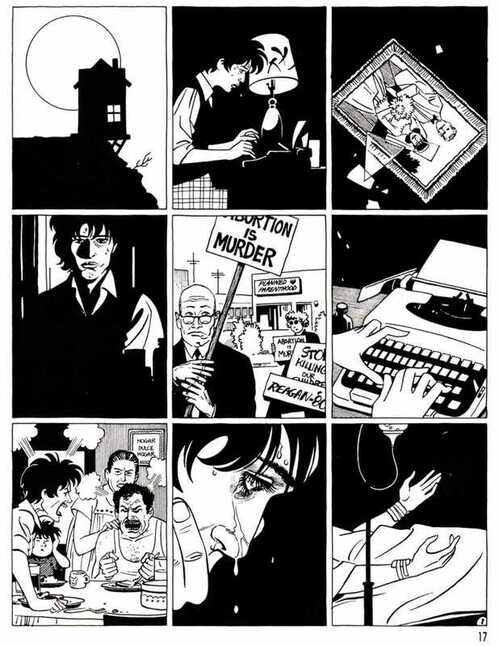

In “Flies on the Ceiling,” the narrative is likewise ruptured and in this case, charged with Mexican-Catholic visuals. Jaime Hernández uses the aesthetic resources of comics to foreground Isabel’s Chicanidad at a point where her wound is intrinsically embodied–during an abortion.1 The precarious conditions of her abortion are shown in the images of dehumanized bodies and animalistic portrayals of her emotional/mental illness. These evoke Chicana imagery where Judeo-Christian and pre-Columbian myth conflate. In stark contrast with this scene is the opening page of the story, where the middle panel shows an American Planned Parenthood office surrounded by white and/or male protesters. This early panel suggests that Isabel’s abortion actually took place in the pulchritude of an American clinic, where her decision is questioned in ethnically-distant, mostly political terms (note the “Reagan–‘80” sign). However, it is only on pages 10-12 where we see the abortion through her lens. Even though she has had an abortion in a first world clinic, her embodied and heartfelt experience of the abortion is encoded in the rupture. The rupture, connecting the beginning of the story and the chaotic fever dream in a relationship of arthrosis, shows the protagonist’s traumatizing experience through a third world lens.

In my analysis, Juan Mah y Bush’s use of “heartfelt awareness” serves as a mode of perception: one that arranges and rearranges our hierarchy of values, our seriality, sequencing, when we engage in an aesthetic struggle. I argue that this comprehensive understanding of “the conceptual alliance among aesthetics, struggle, and heartfelt awareness” is necessary because having remedied the disarticulation of this triad, there is a better chance to comprehend sensibilities of struggle in both the Chicana and her peripheries (101). In these and other ways, both graphic narratives use visual elements to thematize intersections of gender/sex and ethnicity, and to show said intersection as a generative site for alternative forms of relational knowledge for women.

Notes:

1. In this context “wound” has an open meaning that encompasses the physical, the psychological, and the spiritual among other elements of Chicana intersectionality. By using “wound”, I am preliminarily evoking Gloria Anzaldúa’s theorizing of the wound as the emotional residue of the borderland; "la herida abierta" which splits and stakes the Chicana in multiple ways (24-25). However, I plan on expanding this reading in my dissertation by including the voices of other Chicana and Latina feminists, and therefore, this section is still a work in progress and well beyond the scope of this blog-length essay.

Works Cited

Ellwood, Robert S. “Shinto and the Discovery of History of Japan.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 41, no. 4, 1973, pp. 493–505. Groensteen, Thierry, Nick Nguyen, and Bart Beaty. The System of Comics. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2018. Print. Hernández, Jaime. “Flies on the Ceiling”. Love and Rockets. 29. (1988): 17-31. Web archive. Mah y Busch, Juan D. “The Importance of the Heart in Chicana Artistry: Aesthetic Struggle, Aisthesis, “Freedom””. The Un/making of Latina/o Citizenship: Culture, Politics, and Aesthetics, 2014. Print. McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. Print. Tamaki, Mariko and Jillian Tamaki. (2008). Skim. Toronto: Groundwood Books. Print. Camila P. Gutiérrez-Fuentes is working towards a dual-title Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and Visual Studies at Penn State. Her research examines aesthetic lineages and migrations across women’s comics cultures from Japan, The United States, and Latin America (mainly Chile and Mexico.) She has taught undergraduate courses in World Literature, Video Game Culture, Graphic Novels, and Virtual Worlds. In her extracurricular work, she serves as president of the Liberal Arts Collective at Penn State, and is a producer of their podcast Unraveling the Anthropocene: Race, Environment, and Pandemic. Comments are closed.

|

AboutDue to the ongoing pandemic crisis, ICAF was forced to cancel its events at the 2020 Small Press Expo. Over the next 16 weeks (give or take), we will be publishing Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed