remus jackson & F. Stewart-TaylorGraduate students at the University of Florida Despite raising pressing questions about representation and embodiment, trans autobiographical comics are understudied in both comics and trans studies. As comics theorists Elizabeth El Refaie and Hillary Chute have noted, the formal strategies for rendering the self inform the kind of “self” expressed on the page. Trans artists' presentation of self on the page can both describe the creator's phenomenological experience as subjects of coercive gender systems and the practices of resistance and hope that exceed these systems. Following José Esteban Muñoz, moments in these texts are utopian, proposing a future already germinating in the present where possibilities for gendered subjectivity exceed coercive systems. After a methodological overview, we’ll use a trans phenomenological framework to read two comics by Carta Monir. We gesture to possible uses for other texts, including the network of small press comics around Monir’s publishing company, Diskette Press.

Adrienne ReshaPh.D. candidate in American Studies at the College of William & Mary. Since the 1940s, American comic book creators working in the superhero genre have demonstrated a fascination with an ambiguous and amorphous East, including the Arab majority nations of the Middle East and North Africa. While that early fascination resulted in a number of superheroes whose power sets and personas were derived (however loosely) from Egyptian mythology, it did not produce Arab superheroes. Instead, Golden Age characters like Hawkman, Doctor Fate, and Ibis the Invincible were ancient Egyptians, wielders of ancient Egyptian (magical) artifacts, or both. Over eighty years, the origins of Hawkman have alternated between ancient Egypt and the planet of Thanagar, but the character has never been made Arab American. After 9/11, the Egyptian American Danny Khalifa inherited the Ibistick and became Ibis the Invincible. After the Arab Spring protests began in late 2010/early 2011 (beginning in Egypt on January 25th, 2011), the Egyptian Khalid Ben-Hassin and the Egyptian American Khalid Nassour were made to wear Helmets of Fate, the former outside of DC Comics’s primary continuity and the latter within it. The origin stories of Egyptian American legacy heroes, Khalifa and Nassour are examples of repatriation: in them, fictional Egyptian artifacts from the Golden Age are given to newly created Modern and Blue Age Arab American characters.

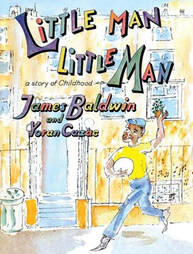

Maite UrcareguiDoctoral candidate of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara.  James Baldwin and Yoran Cazac’s Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood is Baldwin’s love letter to Harlem and to his nephew, Tejan, for whom the story was written. The illustrated children’s book, which was marketed as “a child’s story for adults” on its original jacket cover (1976), follows a day in the life of four-year-old TJ as he moves throughout his Harlem neighborhood with his friends WT and Blinky. While the story could be categorized as an illustrated book, I purposefully place it within a capacious definition of graphic narrative and, thus, in the purview of comics studies. The story places images in intricate spatial relationships, at times creating panel-like structures, that exceed the illustrative and become integral to how the text creates meaning. Through its visual form, Baldwin and Cazac’s graphic narrative make visible how political geographies of race, particularly architectures of surveillance and policing, contour TJ’s experience with space. “The Peace We Find in Battle”: Gender and Violence in Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel Comics11/5/2020

Carolyn CoccaProfessor of Politics, Economics, and Law at the SUNY, College at Old Westbury The use of violence by female superheroes has been written about mostly in terms of its subversion of dominant cultural narratives of gender, as well as in terms of readers/viewers’ pleasure and feelings of empowerment. I would argue, further, that for those who find the subversion of gendered norms discomfiting, the palatability or popularity of female superheroes’ violence also lies in stories that: 1) conform them to raced and classed notions of gender performance, 2) present them as seemingly naturalized to such behavior because they were born to it via an alien and/or exoticized monoculture, 3) accentuate their similarities to popular male superheroes, and 4) surround them with familiar military tropes and trappings. The subversion of gender norms attracts a more progressive audience; the containment of that subversion through these techniques attracts a more conservative audience, thus ensuring marketability across the political spectrum.

|

AboutDue to the ongoing pandemic crisis, ICAF was forced to cancel its events at the 2020 Small Press Expo. Over the next 16 weeks (give or take), we will be publishing Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed