José AlanizProfessor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures - University of Washington, Seattle

Widely regarded as the “father” of Armenian comics, Yerevan-based Tigran Mangasaryan has been producing graphic narrative works since the late 1980s. Since 2005 he has devoted several graphic novels to the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1917, one of the 20th-century’s greatest tragedies, in which over one million Armenians died at the hands of the Ottoman Turks (many modern-day Turks either dispute these figures or point to similar atrocities committed against their own people at the time, or both). Public remembrance of those events more than a century ago remains a pillar of Armenian identity formation, in support of which it mobilizes numerous types of media, both within and without the country’s borders. As described by Roxanna Ferllini:

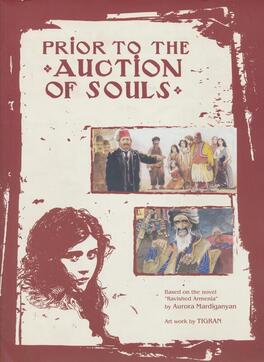

Diasporic communities have been able to develop and maintain cultural and national identity via a series of mnemonic devices, such as historical studies, publications in books, magazines, and newspapers, collections of photographs, memorials, oral histories, and the staging of commemorative events. This kind of “memory work” has served to keep intact Armenian heritage, language, belief systems, sociocultural practices, and maintained an active remembrance of the genocide (“Armenian”: 357-358).  Cover to Tigran Mangasaryan’s Prior to the Auction of Souls (2014). Cover to Tigran Mangasaryan’s Prior to the Auction of Souls (2014).

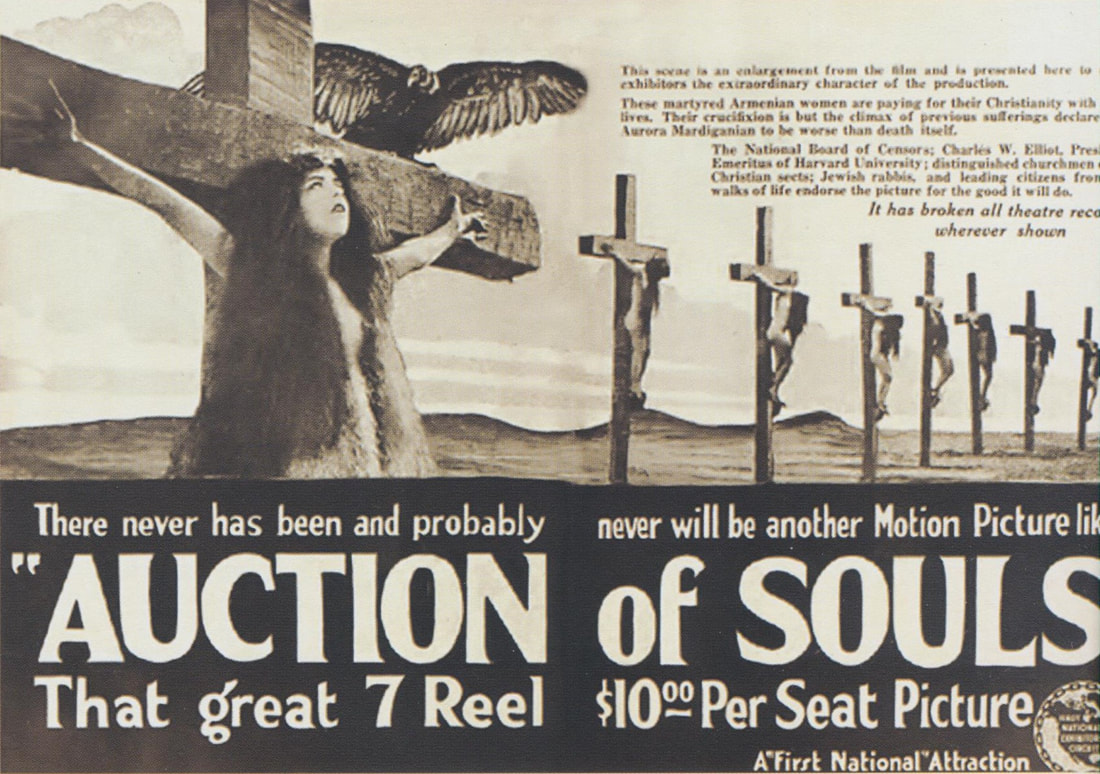

Mangasaryan’s Prior to the Auction of Souls (2014) adapts one of the best-known instances of such “memory work”: Aurora Mardiganyan’s testimonial Ravished Armenia (1918), which depicts in harrowing detail the loss of the young Aurora/Arshalouis’ Armenian family during the genocide and her escape to the USA. The 17-year-old Mardiganyan’s account became the basis for the film Ravished Armenia (aka The Auction of Souls), produced in 1918 to raise funds for victims. The film starred Mardiganyan herself, re-enacting her own traumatic experiences before the camera (see Demoyan/Abrahamyan).

Comparable in some respects to Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1986-1991), both in its unflinching representation of historical atrocity as well as its exploration of memory production/ narrativization and its effect on others, Tigran Mangasaryan’s work lends itself well to a reading framed by Marianne Hirsch’s concept of “postmemory.” In particular I want to highlight the generative impetus of postmemory for those traumatized by experiences which they themselves did not live through: Postmemory’s connection to the past is […] not actually mediated by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. To grow up with such overwhelming inherited memories, to be dominated by narratives that preceded one’s birth or one’s consciousness, is to risk having one’s own stories and experiences displaced, even evacuated, by those of a previous generation. It is to be shaped, however indirectly, by traumatic events that still defy narrative reconstruction and exceed comprehension. These events happened in the past, but their effects continue into the present (Hirsch, “Generation”: 107).

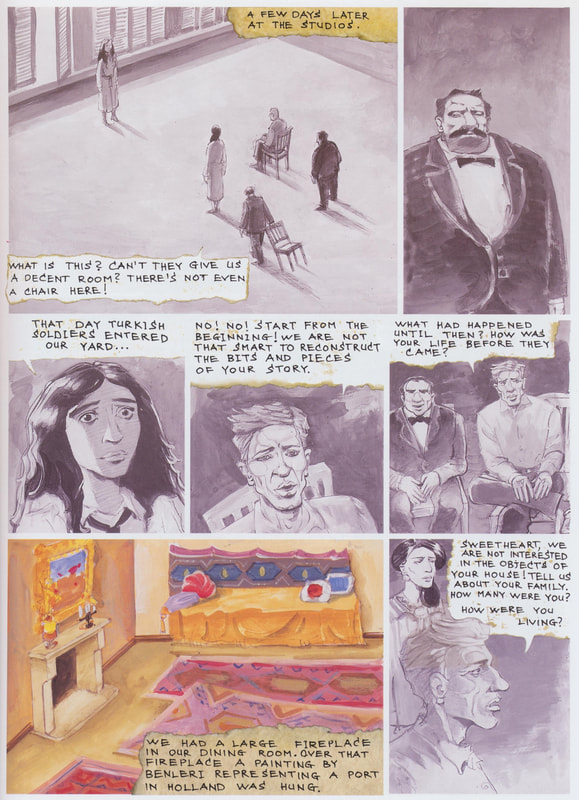

The collaborative, communal, constructed nature of history plays a central role in Mangasaryan’s Prior to the Auction of Souls, complicating the notion that traumatic events “defy narrative reconstruction.” Aurora, as if in front of an audience, tells her story in a large hall to a small group of people that includes a film director. Mangasaryan depicts these present-day framing scenes in the USA in a black and white wash technique, while Aurora’s narrated memories appear in vivid color – making them more “lifelike.” Furthermore, the “audience” constantly interrupts, peppering her with questions, prompts, commentary and off-the-hip story editing (see Fig. 3). For example, the director demands: "No! No! Start from the beginning! We are not that smart to reconstruct the bits and pieces of your story […]Sweetheart, we are not interested in the objects of your house! Tell us about your family. How many were you? How were you living?" (3).

Later, after the girl recounts a particularly gruesome atrocity, a staff member says, “Calm down, Aurora. Let’s give her a break” (47). The filmmakers, taken aback by the unending parade of murder and violation (see Figs. 6&7), themselves need respite. At one point the director says, “That’s enough! I will not put this scene in the movie.” But a burly man with a cigar (later revealed as the producer) thinks to himself, “You will. This will be the most interesting scene[,] where God has gone mad” (31). In such episodes, Prior to the Auction of Souls conveys both the potential trauma of an engagement with history, as well as the intensely social nature of historiography, how the narrative comes about through a process of negotiation – and sometimes, brute imposition.

The reader sees how said trauma manifests as postmemory when the disturbed director rushes home to gaze at his sleeping young son (see Fig. 8). He thinks, “Thank God we’re living in America!” That “present-day” panel, as noted, appears in black and white. The color panel adjacent to it duplicates the composition, only now showing Aurora/Arshalouis’ father looking at his own son, whom he will soon kill in an act of defiance against the Turks (19). “I simply [can’t] stop thinking about that production,” the director later tells his wife. “I don’t know how to start and how to end. I am being terrified about you and little Mickey” (37).

Prior to the Auction of Souls exemplifies the strategies pioneered by Mangasaryan to conceive, produce and market adult-oriented graphic narrative in Armenia, at a moment when this small former Soviet Republic’s comics industry is in its earliest stages of becoming. More than that, Mangasaryan’s graphic biography explicitly participates in the advancement and global dissemination of the important “memory work” pertaining to the genocide, i.e., to particular versions of national historical trauma which as Ferllini argues play a crucial role in modern Armenian identity.

As Mangasaryan told an interviewer: “[T]he most important thing is the preservation of one’s language and culture. […] And for the preservation of your culture, your history, you need to use all means available. Drawn stories are now very relevant to this mission” (Kunin, “Tigran”).

Works Cited

Demoyan, Hayk and Lousine Abrahamyan. Aurora’s Road: Odyssey of an Armenian Genocide Survivor. The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, 2015. Ferllini, Roxana. “The Armenian Genocide: Forensic Intervention, Narrative, and the Historical Record.” Excavating Memory. Ed. Maria Theresia Starzmann and John R. Roby. University Press of Florida, 2016: 357-375. Hirsch, Marianne. “The Generation of Postmemory.” Poetics Today. Vol. 29, No. 1 (Spring, 2008): 103-12. Kunin, Aleksandr. “Tigran Mangasaryan: obraz novogo romana.” Territoriia L (May 17, 2017). http://gazetargub.ru/?p=5905. Mangasaryan, Tigran. Prior to the Auction of Souls. Self-published, 2008. José Alaniz, professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Department of Comparative Literature (adjunct) at the University of Washington, Seattle, has published two books, Komiks: Comic Art in Russia (University Press of Mississippi, 2010) and Death, Disability and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond (UPM, 2014). His research interests include Death and Dying, Disability Studies, Eco-criticism and Comics Studies. Current book projects include Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia. His comics have appeared in The Stranger, the Seattle anthology Dune and Tales From La Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology. Comments are closed.

|

AboutDue to the ongoing pandemic crisis, ICAF was forced to cancel its events at the 2020 Small Press Expo. Over the next 16 weeks (give or take), we will be publishing Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed