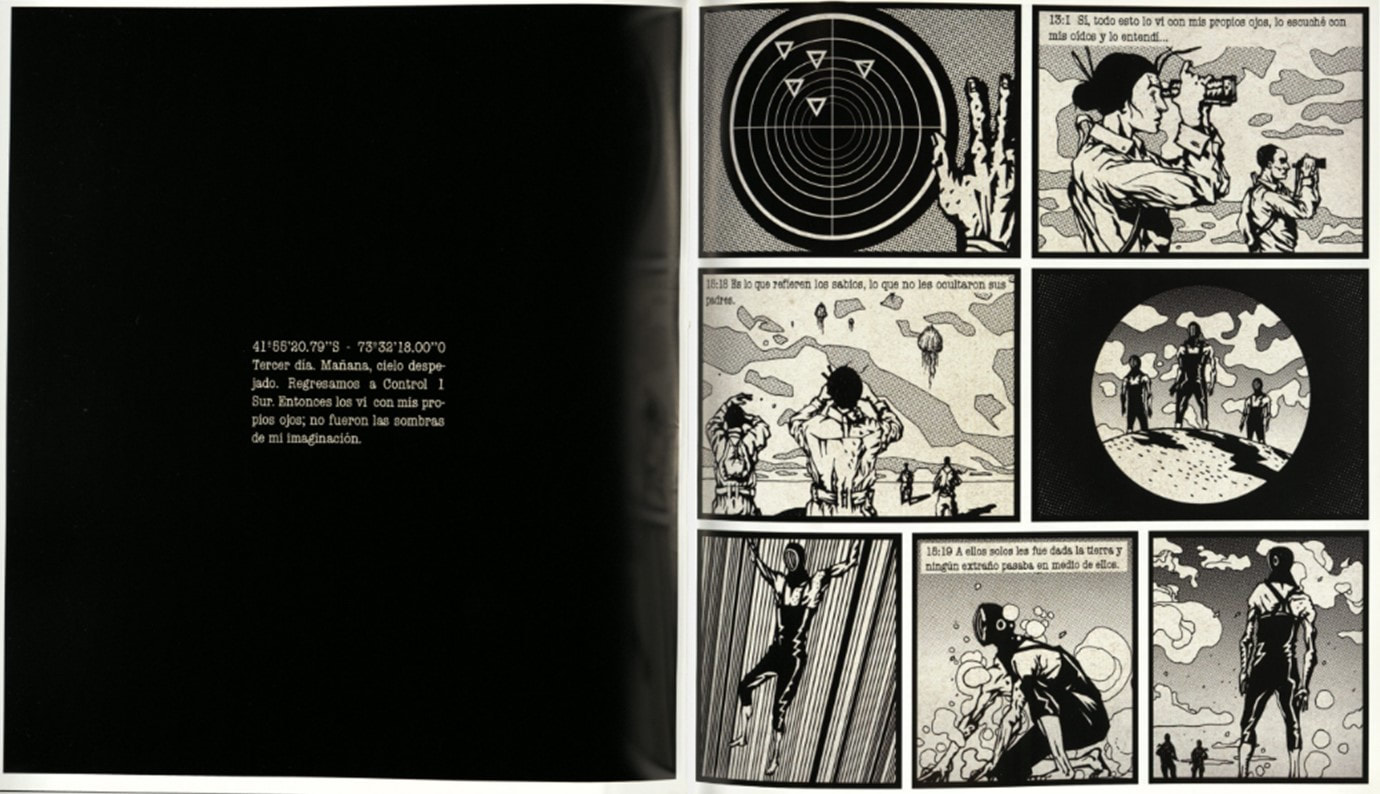

Irenae AigbedionPhD candidate, Department of Comparative Literature at Pennsylvania State University With its opening conceit—an aerolite crashing into Earth and the establishment of an altering-reality-zone—Alexis Figueroa and Claudio Romo’s 2009 graphic novel Informe Tunguska immediately pulls readers towards two distinct frames of reference: history and science fiction. “Tunguska” points to the mysterious meteorite collision that occurred in 1908 near the Stony Tunguska River in Russia, while the reality bending area calls to mind “the Zone” from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film, Stalker. Employing these referents, the text also turns us towards political history, linking the fictional crash and subsequent government investigations of the fallout to the 1973 coup d’état in Chile and the resultant Pinochet dictatorship which, like the mysterious zone, fundamentally altered the lives of the Chilean people. Although reading this text through the lens of political history is highly encouraged within the text itself and would lead to fruitful interpretations, the overabundance of references within the graphic novel resists a totalizing reading that would reduce the entire text to a historical interpretation. Resisting closure, Informe Tunguska provides us with a branching network of references, which, if followed, congregate at the heart of the text, at the epicenter of the crash. Edward King and Joanna Page would argue that such an understanding of the text favors a semiotic reading of Informe Tunguska that discovers the “shared forms that transcend the boundary between humans and the non-human world” (174). One such thread is the presence of religion, my focus in this short piece. Not only does the Christian Church haunt the text as a suspicious institution capitalizing on the fallout from the crash, but focusing on Chapter 10, we note that the dialogue comes from a more recent edition of the Bible which purportedly draws on the original textual sources for its newer, more accessible translation. Borrowing from Darcy Orcutt’s theoretical connections between comics and religion and from Edward King and Joanna Page’s posthumanist, ecocritical reading of Informe Tunguska, I argue that the religious references—particularly to the Book of Job which structure Chapter 10—serve as a reminder of the as of yet unknowable nature of the posthuman and of the crippling limitation of human perception. Citing Christian scriptures, alongside literary, historical, and ecological references, this graphic novel seeks to fill an epistemological gap and to represent a human reaction to a confrontation with the very limits of humanity and human perception. In Chapter 10, two researchers, Sebastián, Erica, and two guards come across a group of monsters, some humanoid, others massive airborne creatures. The humanoids kill Erica and the two guards but leave Sebastián alive. No character speaks or utters a sound in the chapter; the narration in the panels, quotations taken from various chapters in the Book of Job, corresponds to and complicates the action in the narrative. It seems that the main thrust here is God’s unfathomable, undecipherable wrath and power; what is chronicled in the series of images (and reinforced through the text) is an overwhelming, unintelligible, supernatural experience. Despite the layer of unintelligibility, Sebastián notes, “...Entonces los vi con mis propios ojos; no fueron las sombras de mi imaginación.” (Figueroa and Romo) Hence, he simultaneously warns readers that what follows may seem untrue. The next caption, “13:1 Si, todo esto lo vi con mis propios ojos, lo escuché con mis oídos y lo entendí” appears as a continuation of Sebastián’s reflections, noted with minute markers; his eyes bring him information (via binoculars), as well as his ears). His knowledge emerges through sensory perception. These words, however, belong to Job in the Old Testament. As the intertext of the chapter, the Book of Job highlights an encounter with the unintelligible and the limitations of human perception. The narrative voice in “Leviatán” does not only come from Job, but also draws quotes from God and Eliphaz the Temanite (who himself is citing a voice in a dream). This borrowing creates a seemingly unified voice from a plurality of speakers, yet, once we distinguish the multiple voices behind the narration, it becomes a chaotic network of positions clashing with each other even within the source text. Such chaos challenges the identification of each speaker in this chapter (or in the whole comic) and, even finding the voice’s source, the connection among speakers could be irretrievable. Finally, the Bible’s translation quoted within the text is worth mentioning here. The verses here come directly from El Libro del Pueblo de Dios, the 1980 Spanish language translation of the Bible compiled by Presbyterians Armando J. Levoratti y Alfredo B. Trusso. Released in Argentina and adopted later in Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay, this version of the Bible is marketed as the approved translation for liturgical use in the Conferencias Episcopales del Cono Sur encompassing the four countries. It is also the version of the Bible currently hosted by the Vatican’s official website. What is fascinating about El Libro del Pueblo de Dios (ELPD) are the stark differences not only between it and the widely used King James Version (KJV) or the New International Version (NIV), favored by English speaking Catholics and Protestants, but also between it and other Spanish translations of the text. Most notably, in this version, there are extended chapters, verses that appear to be out of order in comparison to the KJV or the NIV (and potentially the NVI, the Nueva Versión Internacional). We should note that ELPD can be understood as a firmly Latin American edition of the Bible, using Latin American, not Peninsular/Castilian forms of Spanish. Adopting this version of the text (published in the middle of the Argentine military dictatorship) is another way of connecting the distinct yet parallel histories of Chile and Argentina and making room for another possible reading of the inclusion of religion in Informe Tunguska: a move to carve out a distinctly Latin American history decoupled partially from the Spanish conquest. Analyzing religion as one interpretive tool offered in Informe Tunguska facilitates a deep engagement with the text that exponentially expands the dense network of references. Works Cited Figueroa Aracena, Alexis, and Claudio Romo. Informe Tunguska. LOM Ediciones, 2009. Orcutt, Darby. “Comics and Religion: Theoretical Connections.” Graven Images: Religion in Comic Books and Graphic Novels, edited by A. David Lewis and Christine Hoff Kraemer, Continuum, 2010, pp. 93–106. Page, Joanna and Edward King. “Post-Anthropocentric Ecologies and Embodied Cognition.” Posthumanism and the Graphic Novel in Latin America. UCL Press, 2017, pp. 163–180. Irenae Aigbedion is a PhD candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature at Pennsylvania State University. Her research focuses on representations of blackness and racial identity in contemporary literature and visual culture from the Americas. Focusing on a corpus of comics and films from the United States, Mexico, and Brazil, her dissertation examines the ways in which images of blackness create and sustain a cultural imaginary of black identity/identities throughout the Western Hemisphere. Her work has been published in the International Journal of the Classical Tradition and in ImageText. Comments are closed.

|

AboutDue to the ongoing pandemic crisis, ICAF was forced to cancel its events at the 2020 Small Press Expo. Over the next 16 weeks (give or take), we will be publishing Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed